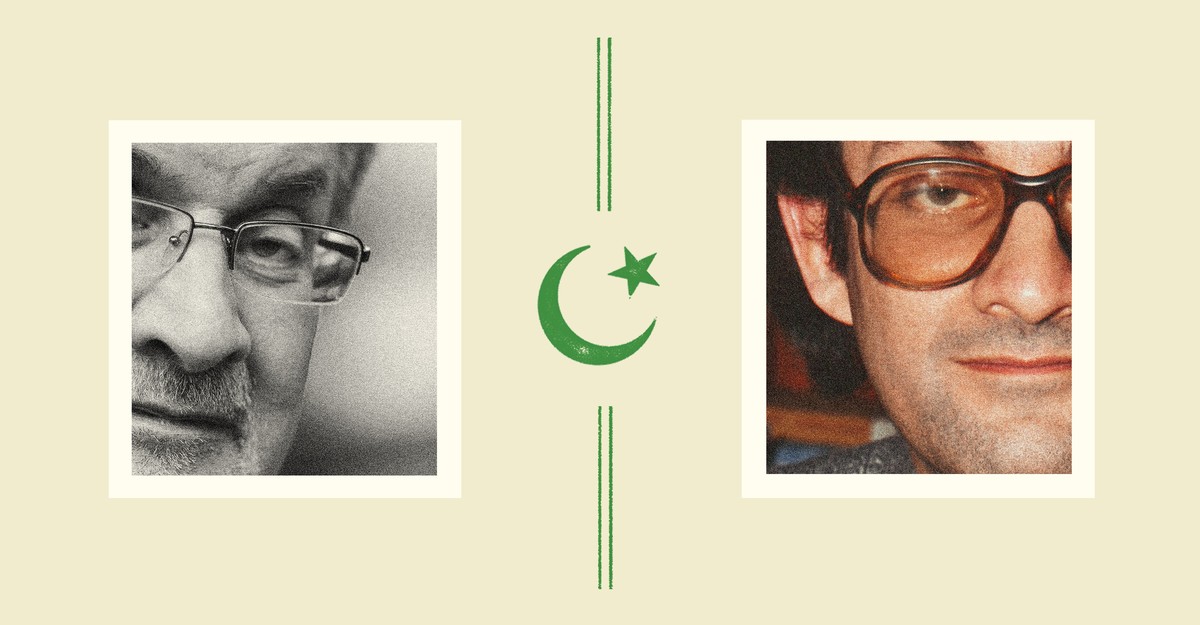

In the spring of 1989, a 21-year-old Iraqi university student named Ali returned home and made a shocking discovery: on the living room table of his family’s house was a copy of satanic verses. A friend of Ali’s father had smuggled Salman Rushdie’s controversial book from London, removing its distinctive blue cover and hiding it in his luggage. It was like finding a bomb.

Ali, a shy and curious young man with a passion for reading, was delighted to hold such a forbidden object. Ayatollah Khomeini had recently issued his famous fatwa sentencing Rushdie to death, and protests by Muslims were erupting around the world against what they saw as an intolerable insult to their faith. Crowds gathered in public squares to burn the book; bookstores were burned down. Ali’s father, a relatively liberal man, had taken a risk just by letting a copy into his home.

Ali, who left Iraq more than a decade ago, told me recently that he still remembers the intense excitement he felt when he first touched the pages. But satanic verses was not an easy novel. Ali had studied English for years, but Rushdie’s language was sophisticated and inventive, so much so that reading it required great mental effort and frequent reference to the Oxford English Dictionary, which he kept with him. He was taking notes as he went, partly out of habit and partly because his father’s friend wanted to return the book to him in a week. When he finished it, he was exhausted.

What Ali remembers most is a sense of admiration for the depth of Rushdie’s knowledge and the richness of his imagination. Rushdie had used religious names and stories like scraps of fabric and woven them together, past and present, into a bizarre, multicolored garment. It was pretty clear that Rushdie was deliberately provoking Islamic sensibilities with his overlapping of the sacred and the secular. But Ali, a practicing Muslim at the time, was not offended. It seemed to him that Rushdie’s intention was not to spit in the face of believers but to create stories that teased and fused the cultural narratives of East and West. The larger message of the book, as far as he could understand it, seemed true to Ali: “Let the good and the bad mingle. They sometimes fight, but they can’t always be easily separated.

Ali was perhaps exactly the kind of reader Rushdie most hoped for, someone who would be both challenged and inspired by his fictions. Unfortunately, satanic verses had something of the opposite effect for much of the world, a hardening of the outlook. The outcry created a pattern that repeated itself with depressing regularity in the decades that followed, a kind of passion game that entrenched resentment on all sides. A sacrilegious image or comment or work of art made in Copenhagen or London is discovered and then rebroadcast in Cairo or Tehran. Threats are made, protests ensue, people die.

It is tempting to see these outbreaks as an inescapable feature of globalization, a measure of the gap between a secularized society, where the idea of blasphemy is a joke, and a more traditional society, where there remains a powerful taboo enshrined in law. . But conflicts are often amplified by an opportunistic cleric or politician looking for excuses to stir up anger and throw red meat at their political or religious base – it’s always about men. These demagogues are enabled, to some extent, by the relative absence of high-profile readers like my friend Ali in the Middle East. Go to a library or bookstore in this part of the world and you will see how limited the offerings are.

They may not know it, but Middle Easterners are surrounded by more dangerous local provocateurs than Rushdie. During the years I lived in Baghdad, a book began making the rounds for the country’s shrunken elite: The personality of Muhammad or the elucidation of the holy enigma, by Iraqi scholar and poet Maruf al Rusafi. The book presents a demythologized reading of Muhammad’s life and work, arguing that he was a great political and military leader, but nothing more. Rusafi’s book was written at the beginning of the 20th century. If published today, the author would probably need an army of bodyguards.

There are many other examples. The medieval Persian poet Abu Nuwas wrote poems about wine drinking and sex with men and women; he often invokes Quranic imagery in a wry way that today would seem outrageous. But no one has issued a fatwa against these writers. A bronze statue of Rusafi has stood unmolested near a bridge in Baghdad for decades, surviving several wars and invasions. As for Abu Nuwas, he is venerated (but little read) to this day in Iraq. One of Baghdad’s most beloved and beautiful streets along the Tigris is named after him. When Abu Nuwas died in the year 814, the reigning caliph declared “God’s curse on anyone who insulted him”.

Shortly after meeting Ali, one of the deadliest blasphemy fits erupted, sparking a series of cartoons published in Denmark in 2005 that depicted the Prophet Muhammad. We worked in the Baghdad office of The New York Times, me as a journalist and him as an editor. Ali is an instinctively gentle and kind man – it’s one of the first things you notice about him – and he was horrified by the violence of the protests. But he was also upset with the way the controversy was framed in the Western press. He felt there was an absolutism over free speech which made the problem worse. I remember he asked me if it wouldn’t be possible to create some kind of religious exception to freedom of expression, to avoid conflicts like this.

I got the impression that Ali was trying to balance his own Muslim upbringing with the more secular perspectives he had been exposed to as an adult. It was not easy. The years following Rushdie’s fatwa brought a series of wars and catastrophes that sharpened the sense of a collision between East and West: the Gulf War of 1990-1991, the rise of al -Qaeda, the September 11 attacks, the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In the years since our conversation about the Danish cartoons, Iraq descended into civil war. Ali reluctantly joined the wave of refugees fleeing the country. He was luckier than most; with his superb education and vast network of friends, he reached the United States and secured a teaching position at one of the best universities in the country. He was not unaware of the irony that his country’s collapse had given him a better life – in many ways – than he could have had in Iraq.

Ali remained an admirer of Salman Rushdie. About a decade ago he went to a public reading and was disappointed to find that the novelist would only appear via video link due to the ongoing danger to his life. During the isolation that accompanied the pandemic in 2020, Ali told me he paid for a subscription to an online writing course featuring Rushdie. “I watched it for hours,” he said.

Over the years, Ali’s view of free speech has changed. He came to feel that “words can only be fought with words”, as he told me. He resented the arrogance of religious figures in any culture who value their sensibilities more than human lives. He also felt embarrassed by the way Arab and Islamic publishers censor and hijack their own literary tradition. He told me how he bought a copy of Thousand and one Night, the great collection of medieval tales, during a trip to Mosul with his aunt when he was 9 years old. He didn’t understand the sexual references in the stories, and when he asked his parents, they just smiled and told him to keep reading. Today, Ali says, it would probably be difficult to find such an uncensored version in an Arabic bookstore. Many contemporary authors who write on sensitive subjects have their books banned.

In a sense, the attempt on Rushdie’s life marked the end of the book for Ali. He had first been challenged to think beyond the Islamic orthodoxy of his childhood by reading satanic verses. Now, reading Arab media coverage of the attack, he was sickened and furious to see some people praising the would-be killer and calling him a hero. The entire 33-year campaign against Rushdie, he felt, was not driven by genuine religious sentiment, but by cynical political agendas and sectarian grievances. He had become a full-fledged supporter of free speech and an advocate for Rushdie and others like him.

But as Ali’s views changed, he realized a curious irony: many people around him in the West were moving in the opposite direction. At the university where he now teaches, considerable effort is made to respect the beliefs and sensitivities of students, in order to avoid offense. Speakers who might disturb students are less likely to be invited. The goals are incremental, but the methods remind him of the theocrats of the world he thought he had left behind.

“It’s strange,” Ali told me. “Nowadays, if you want to criticize Jesus, that’s fine. But if you criticize Muhammad, well, that might be a problem. Because people will say you offend Muslims.

So they will. The same demands for “respect” will come from other believers, sacred or lay. Rushdie’s insistence on the right to blasphemy has always been ecumenical. “If you’re offended,” he once said, “that’s your problem.”