After my first look at the fall college press offerings, around Memorial Day, nearly 30 more catalogs came out. So here’s another quick scan of the horizon, looking for patterns or themes. Many important and interesting books are planned for publication. No claim to a representative survey, let alone completeness, is implied – just a brief overview of some volumes of general interest.

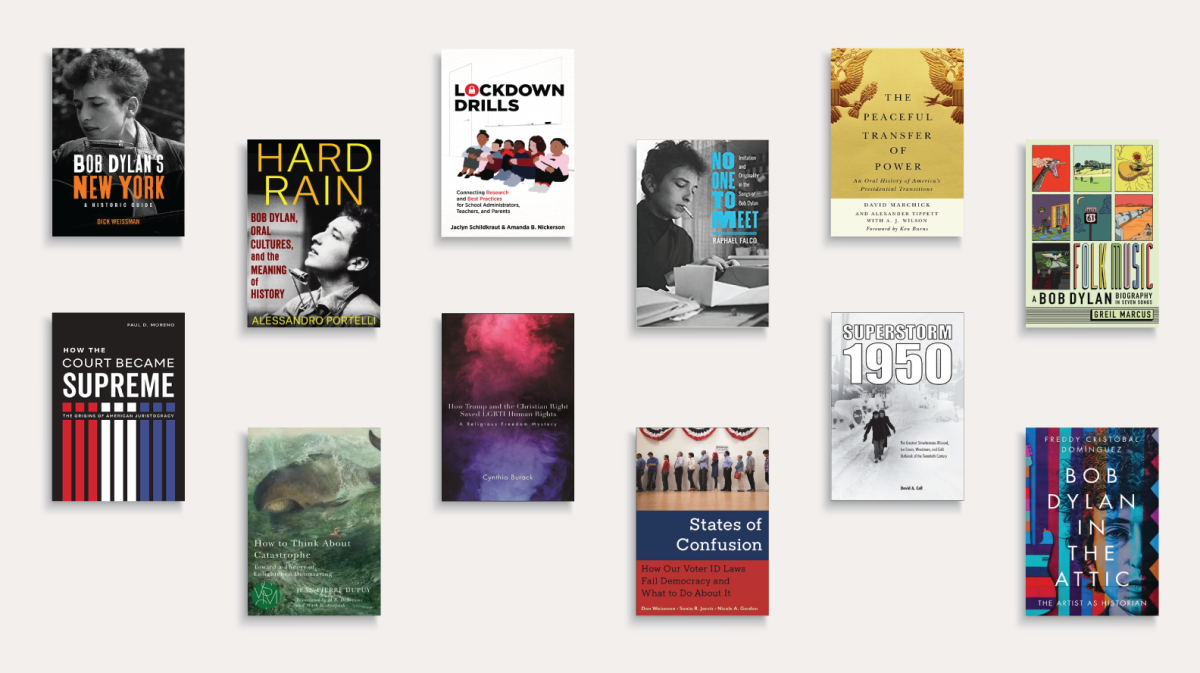

Many headlines seem torn from today’s headlines, with The Peaceful Transfer of Power: An Oral History of American Presidential Transitions (University of Virginia Press, October) for exemple. Throughout the year leading up to January 2021, the authors – David Marchick, Alexander Tippett and AJ Wilson – ran a podcast titled Transition Lab featuring “interviews with scholars, journalists, government officials and — most importantly — participants in every transition from Ford-Carter to Trump-Biden.” (All quotes here are taken from the publishers’ catalogs or websites.) Their book blends podcast exchanges into an account of “the long history, complexity, and current best practices associated with this most vital democratic institution.”

The federal judiciary was once considered virtually immune to electoral pressures, but the How the Court Became Supreme: The Origins of American Juristocracy (Louisiana State University Press, September) focuses on the increasing entanglement of the Supreme Court with the executive and legislative branches. Despite the constitutional provision of “a host of safeguards to prevent judicial excesses”, the court “effectively possesses[es] the ability to monitor elections and choose presidents”, arguably “harmful rather than strengthening constitutional democracy”. The author “tells the story of the origin and development of this problem, proposing solutions that might compel the Court to assume its more traditional role in our constitutional republic”.

Looking closer at the urn itself, Don Waisanen, Sonia R. Jarvis, and Nicole A. Gordon Confusion States: How our voter ID laws are failing democracy and what to do about it (NYU Press, January) finds that “the number of voter identification laws has exploded, limiting the ability of nearly twenty-five million eligible voters to exercise their constitutional right to vote.” Examining “hundreds of online surveys, audits of 150 election offices, community focus groups, and more,” the authors survey 10 states with strict voter ID requirements; they call for “uniform national voter identification standards that are simple, accessible and free”.

As counter-intuitive titles go, it would be hard to improve on Cynthia Burack’s one How Trump and the Christian Right Saved LGBTI Human Rights: A Mystery for Religious Liberty (SUNY Press, August). For the Christian right, treating sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) as a concern to be addressed in US foreign policy was another abomination of the Obama administration – one that their favorite candidate in 2016 would surely put an end to. , once in power. And yet he didn’t. This has never been a priority, and “American conservative Christian officials and elites have failed to do all they can to publicize, curb, defund, and undermine American support for SOGI.” The book offers a case study of “the indifference, lies, and political interests at stake in Trump’s alliance with right-wing Christian elites.”

A Volume Born of Dark Necessity, Jaclyn Schildkraut and Amanda B. Nickerson Containment Exercises: Connecting Research and Best Practices for School Administrators, Teachers, and Parents (MIT Press, September) argues for the importance of such exercises as part of a K-12 system’s emergency preparedness planning. The authors combine “a discussion of the perceptions and psychological impacts of lockdown exercises with scientific research on the extent to which lockdown exercises improve the effectiveness with which individuals respond to a potential threat.” Today’s worst-case scenarios are too common to ignore.

Although the weather is currently on the grill, it is worth remembering the impact of the other extreme. David A. Call’s Superstorm 1950: the largest simultaneous blizzard, ice storm, windstorm and cold epidemic of the 20th century (Purdue University Press, January) recounts how “the greatest storm of the 20th century crippled the eastern United States, affecting more than 100 million people” in November 1950. While “two other storms that have affected the continental United States since then, both hurricanes, surpassed its death toll, “it was ‘the costliest weather disaster when it occurred’ – and a recurrence in the present day “would likely be the costliest weather disaster ever in the United States- United”.

Moving from the particular to the general, we have a translation by Jean-Pierre Dupuy How to think about catastrophe: towards an enlightened theory of catastrophic prediction (Michigan State University Press, November). The author – a co-thinker of the late René Girard, whose concepts of mimetic desire and sacrificial violence have had an interdisciplinary impact – “examines different types of disasters from natural (eg earthquakes) to industrial (eg , Chernobyl) and concludes that the traditional distinctions between them are only blurring day by day. We need “a general theory of disasters – a new form of apocalyptic thinking grounded in science and philosophy”, capable of offering “a new way of thinking about the future by looking at disasters and human response”.

Ezra Pound once characterized literature as “news that remains news”, and Bob Dylan’s apocalyptic dispatch “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” remains as urgent today as when he wrote it 60 years ago . by Alessandro Portelli Hard Rain: Bob Dylan, Oral Cultures and the Sense of History (Columbia University Press, May) actually appeared in late spring, but it belongs in this fall roundup given the remarkable release of college press headlines from the season on the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016. The surreal juxtaposition of Dylan’s imagery in the song, while “relevant to post-nuclear nightmares and 1960s youth movements”, also foreshadows “contemporary concerns about environmental crisis, racism and mass migration while drawing inspiration “from the traditional British ballad ‘Lord Randal’ and the 17th century Italian ballad ‘Il testamento dell’avvelenato'”. Portelli is concerned with “how Dylan was able to use the folk ballad tradition combined with a modern sensibility to creatively question the meaning and direction of the story.

It just so happens that the four Dylanologues with books this fall also focus on his poetic and historical sensibility. Raphael Falco Person to meet: Imitation and originality in the songs of Bob Dylan (University of Alabama Press, October) draws on the songwriter’s “unpublished manuscript excerpts and archival material” to trace “the similarity between what Renaissance writers called imitatio and the way Dylan borrows, digests and transforms traditional songs”.

In Bob Dylan in the Attic: The Artist as Historian (University of Massachusetts Press, December), Freddy Cristóbal Domínguez recalls a warning from Dylan’s first mentor, Dave Van Ronk: “You’re going to be a history book writer if you do these things. An anachronism. Domínguez celebrates what Van Ronk lamented, “offering an in-depth reflection on the musician’s historical influences and practices” and Dylan’s role in “helping listeners think about history and make it in new ways”.

at Dick Weissmann Bob Dylan’s New York: A Historical Guide (SUNY Press, November) “places the beginning of Dylan’s career in the history of Greenwich Village, a hotbed of new developments in the arts”, as well as “the many neighborhoods of the city where Dylan lived and worked”, as well as his stay upstate in Woodstock. The author provides 10 “easy-to-follow walking maps and historical photographs, allowing the reader to retrace Dylan’s footsteps and experience Dylan’s New York and contemporary New York simultaneously.” This is perhaps the first college press book to include its own walking tours.

Finally, Greil Marcus Folk Music: A Biography of Bob Dylan in Seven Songs (Yale University Press, October) is inspired by “Dylan’s ability to ‘see himself in others'” and navigate the “rich history of American folk songs”. In addition to offering “a deeply felt account of the life and times of Bob Dylan”, the author honors his example at a time when “such vast imaginative identification with the other is rare”.